星影の館殺人事件 (Hoshikage no Yakata Satsujin Jiken): A Curious and Curiouser Free Occult Mystery Game

ruh-roh bird monsters are real

Disclaimer/CW: Although this article doesn’t use any grotesque imagery as screenshots for the game, people queasy with such imagery relating to corpses and food should be advised from playing it.

The Not-So Scientific World of Mysteries Now

For better or for worse, the mystery genre is rooted in the optimism of the Enlightenment and rationalism1.

Upon reading works like Sherlock Holmes and Murder on the Orient Express, one gets the impression that amateur detectives with their inductive reasoning and knowledge are backed up by the latest developments on science and technology. Or at the very least, it feels like there’s some rationale behind them. Readers may not know the specialist knowledge that these characters possess, “but it seems like a legitimate scientific procedure”2. The artifice of reality keeps readers engaged with the fiction. They’re ready to learn and perhaps be wowed by the genius of the characters (and the writers). And the catharsis mysteries often give emerges in the form of well-rounded explanations of the ills of societies.

But this verisimilitude may not only prove to be an illusion but it could be a limit on the actually cool parts of mystery fiction. Without retreading too much on what I’ve already written about mystery fiction3, I personally think mysteries today (and crime shows in general) have become too enchanted by scientism and pseudoscience. They’ve lost their focus as a genre for entertainment and are instead reproducing copaganda narratives4. Even if we ignore ideology for a second, these stories are bogged down by jargon and rarely play on the wonders of discovering a dank plot twist. They’re just not fun entertainment anymore.

Japanese mysteries have been grappling with this issue for quite a while. The shinhonkaku movement, for example, examines the foundations of mysteries and find them to be artificial years before people acquired the conceptual language to describe the flaws5. But in their debunking of the genre, they rediscovered their love for mysteries and started approaching them in new, fresh ways. These path-breaking titles reveal that not everything is under the sun.

But do we really have to break new ground and explore uncharted territories? What if do something simpler? What if we take a step back and emulate the past while adding a little bit of that modern QOL?

The World of Occult Mysteries Then

As a fan of everything mystery, I was intrigued by the talk around 星影の館殺人事件 (Hoshikage no Yakata Satsujin Jiken, lit. The Murder Case at Star Shadow Mansion), a free retro mystery game available on several websites dedicated to free games (a paid version includes a walkthrough and an afterword). Developed in five months by the doujin circle Horakai, this homage to works like Famicom Detective Club received praise for being a hybrid of old and new game design sensibilities6.

The game follows “you”, someone commonly mistaken to be a detective, solving a murder case in a mansion on top of a hill. A man was murdered. The Yamamori family and their servants are suspicious as ever. This sounds like a normal mystery game so far — until the title suddenly brings up a mythical beast called the Kowabamidori (声食鳥).

When mystery works incorporate the occult, they tend to be of the Scooby-Doo kind: the perpetrator is using supernatural elements as a facade and if it wasn’t for those meddling kids, they would have committed the perfect crime and buried their sins into the graveyard of urban legends. They remain adherent to the conventions of mystery fiction; anything more would move it into the realms of fantasy. The improbable and the contrived need to be substantive enough to be believable, but it should also be fleshed out as realistically as possible7. In any other game, the Kowabamidori would've been some dude in a bird costume. Or more realistically, someone using the legend to cover up their misdeeds.

But in the world of Hoshikage, Japanese folklore is real. You meet one of the many birds that has allegedly killed the victim. These birds roam in the forest and they mimic the sounds of the human throats they’ve eaten. While they can’t say more than five words, they sound real enough to naive folks. Anyone foolish enough to respond will be attacked and gobbled up by the bird. Hope you’ve got a talisman powered up by the shrine maiden of the family. Otherwise, you might not only die but also have your voice lure another victim to their demise.

And there also seems to be a tenuous but still real connection to a disease plaguing the town downhill. Everyone suffering from it is croaking the same words over and over again, symptoms somewhat similar to the birds. Doctors and researchers don’t know what to make of it.

This interplay of fantasy and mystery is immediately unsettling and more importantly, very unique. Rather than taking established routes, the game dares to take on something rarely examined in mystery games: what if the apparitions haunting mystery games are real? Can we still play out our rational detective fantasies in a game full of real myths? What is there to uncover in a mystery like this?

For the last question, it turns out there’s actually quite a lot.

The Return of Mysterious Mysteries

The best parts of the game deal with this gray zone of myth and logic. To be more specific, Hoshikage recognizes the appeal of its setting comes from this balancing act and will take measures to really bring this aspect out.

As an example, everyone within the Hoshikage Mansion is connected deeply to this legend, so you’re not only figuring out the usual family secrets but also how they tie into this real mythology. Osamu, the head of the family, is tasked to take down all the remaining Kowabamidori. He must always put impressive displays of masculinity in front of his family to reassure they’re safe in his hands, but he will hesitate shooting a Kowarubamidori who happened to mimic his late father’s words. Kozue, the matriarch, wants to know what is wrong with her son, Manabu, and why he displays symptoms similar but not quite to the disease in the town. She wonders if the child inside her will be the same too. And the servants have to defend the mansion with axes and rifles in case the bird comes in to visit them. As denigrated lower-class “members” of the family, they feel conflicted about their duty and purpose protecting the family. The cast is full of more or less sensible human beings who are just doing what they can in this otherwise strange world.

You, the amateur, are also not some by-passer either. Although details are never explicit, you and your self-proclaimed assistant have a spiritual connection to the ghosts around you. The phantasm is ordinary, even logical and understandable, to your eyes.

So, how should you approach this mystery?

While your bag of tricks as a mystery reader may still come in handy in figuring some plot twists out, the cliches that do inevitably emerge feel unique under this new light. Forensics won’t save your ass. Instead, you have to think about the arts of folklore and history. You have to keep revising your understanding of the family history, the Kowarubamidori, and other aspects of the mystery till the end of the game. In other words, you have to keep reassessing this question: how do the facts align with what you know of the fantasy? It’s surprisingly refreshing, perhaps reinvigorating, to think alongside these original rules for the game.

While the simple trick of admitting fantasy into reality is tremendously beneficial to its narrative, there’s another aspect that keeps the mystery alive for me. Hoshikage gets why old games look the way they are — and successfully modernizes it. Its appeal to retro art doesn’t result in the forgery of authenticity; instead, it hearkens to what makes older video games so appealing and creative to this day.

Older games demand their players to imagine the world they’re traveling in. The few assets they do have help, but they act more like clues and fragments of a larger world than something truly immersive. You’re not traversing in the digital terrains of Skyrim, you’re looking at images and text that indicate you’re in a spot. It may therefore be more correct to say that older games construct systems of signs that point to features of a world. They’re abstract in nature due to file size limitations, but they engage the player to fill in the blanks and imagine the world like a tabletop game. Learning to appreciate these semiotic systems and extrapolate in our imagination is virtually necessary if we want to make any headway into these games.

This is perhaps why many indie games with “retro” pixel art aesthetics never really resonated with me. Shovel Knight is most representative here: it’s a game with gameplay decisions that could’ve come out from the NES, but other than that, it has way too much stuff. I’m not just talking about having more than the usual limited color palette; backgrounds tend to have more stuff beyond the typical MSPaint bucket fill and character sprites are more detailed. Nothing is left to the imagination: you can see everything that would’ve been imagined depicted in the pixels.

Under this criteria, Hoshikage shouldn’t feel too retro to me either. It has more content and text than a Famicom disk system game would’ve had as a quick example.

However, I became entranced by the title when I started getting into the game. Movement in the game isn’t visually depicted. Facial expressions are more visceral, but they aren’t animated enough to tell you more than what’s on the surface. And the rooms are just filtered photographs with text descriptions. All these decisions and more ask you to flesh out the world in your mind.

I can’t really imagine what it was like to play games like Portopia Serial Murder Case when they just came out8, but my time with Hoshikage must've been pretty familiar. There was a sense of adventure going through different screens and seeing events happen. When new lines trickle into the screen based on what I input, I get excited and mentally note down any new important pieces of information.

At the same time, the game reduces the jank commonly associated with older adventure games: you have the option to think during your investigations and the game outright tells you which dialog options you haven’t exhausted yet. Its sensitivity to potential slumps in pacing means the game allows the player to remain imaginative without losing focus. If you click too fast, there’s a backlog courtesy of the Tyranoscript engine. There’s few pauses or breaks caused by the player not understanding what to do in the game, just the story unraveling bit by bit.

I also think it’s impressive that it knows when to take off the brakes and simply display grotesque imagery. The victim’s corpse you see throughout the game and a particular scene dealing with food may turn people off, but I find these moments to be effective horror. The atmosphere these scenes conjure is intoxicating: you are reminded how unnerving living in this world is, but you also want to get to the bottom of this. There is clearly a light at the end of the tunnel, but you must first overcome a little bit of the scary stuff.

And you definitely want to see the narrative to the end. The climax of the story feels like something you’d see out of the movies, but it makes the epilogue quite interesting to reflect on. Without giving any spoilers away, I’ll say that I’m glad that the player’s real impact is solving the case and that’s all. It’s up to the family to figure out what they should do with their newfound knowledge about themselves. You’re exiting the stage because you’re simply the detective, not a member of the family. All you can hope is that they become better people.

All in all, Hoshikage will make use of anything old and new to keep the mystery engrossing. Its allegiance to tradition like the three-act structure gives it some leeway in breathing in new things. Indeed, the game knows when to relax and let the formula do its thing, but it will speak up when it does have something new to say. In that sense, the title may have authentically captured the wonders of playing a Famicom mystery game for a modern audience.

All Kana, All Worries

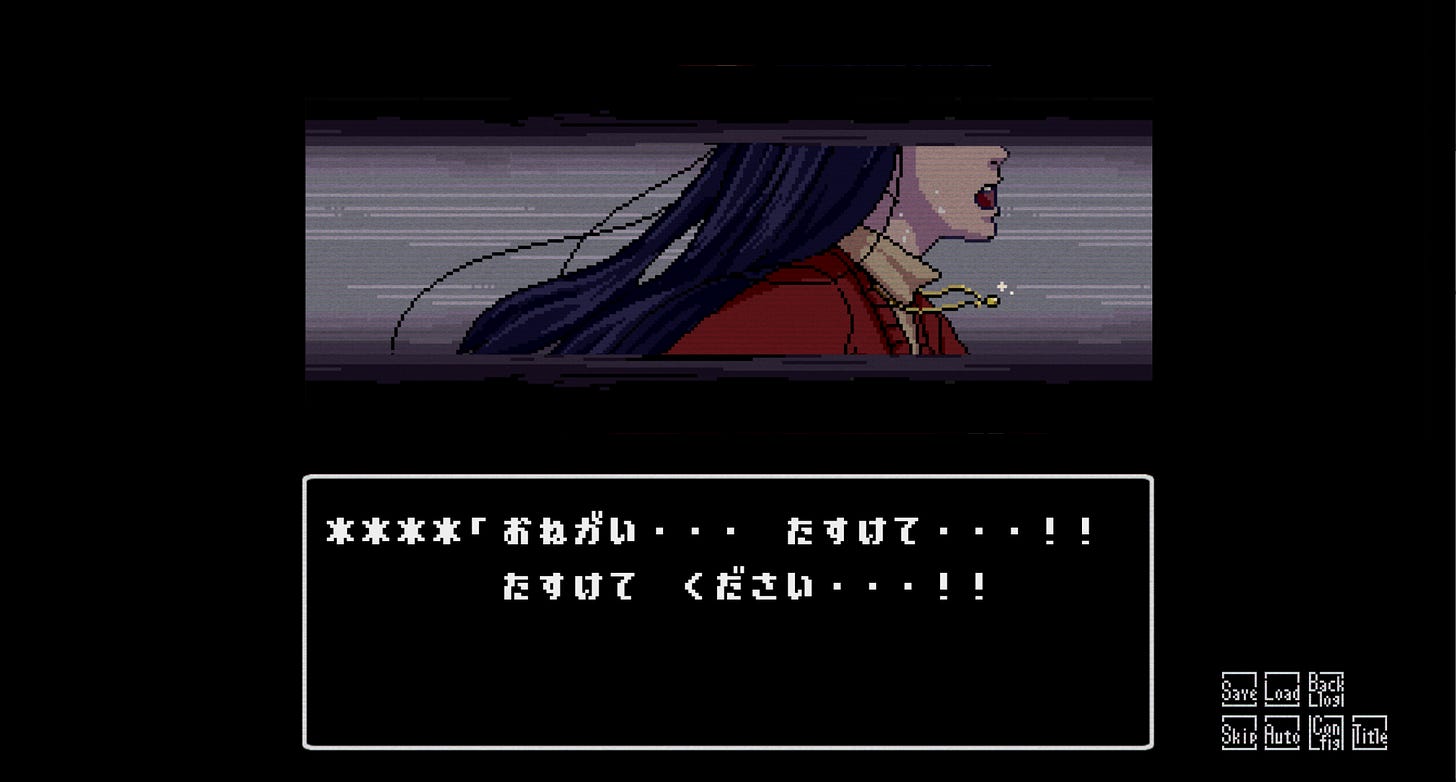

However, as much as it pains me to say this, I recognize that the game has one major flaw that should be noticeable to anyone who knows a lick of Japanese and has been looking at the screenshots: most of the game is written in all-kana.

For those unaware, many old games tend to be in the kana writing system in order to save space. What this means is that players are reading everything in phonetics — imagine reading this article all in IPA or International Phonetic Alphabet — and it is doubly difficult when the story is this dense.

While writing this article, I played Famicom Detective Club: The Missing Heir (ファミコン探偵倶楽部 消えた後継者), an influential 1988 mystery game that’s also written in all kana. The story is fairly simple to follow and doesn’t use much vocabulary that would stump most literate people. I didn’t have difficulty following the story, though I must admit it remained annoying to read anything without kanji.

This is not the case with Hoshikage. The narrative is far too dense to merely be in kana. I've found myself looking up the dictionary for most of the lines I've encountered since these lines are longer than anything in The Missing Heir. I was afraid of missing out on the semantic meaning of these lines. Indeed, I've found myself misreading people's names and what people are saying just because I got lost in the hiragana soup. While this is partially alleviated through glossaries and character bios written with kanji, it remains easy to gloss over infodumps and not get the full flavor of the text9.

For a game that’s trying to make this genre more accessible to younger people, I found it peculiar there’s no kanji option or slider. While I do get the appeal of sticking to the classics, this aspect is honestly one I don’t really miss.

What Makes Things Truly Mysterious?

That said, if you’re willing to endure looking up many words, you’ll definitely be rewarded with a compelling and even emotional narrative that pays respect to the past while carving out something new.

Finishing this game made me rethink what I want from mysteries. If I’m ever writing one, I don’t have to craft some obscure puzzle to amaze my readers. Instead, I should ask what makes a mystery mysterious to me: “What unsettles me? What makes me curious? Why should I care about solving this?”

Mysteries, in the end, are exciting stories about shining light on some unknown. Whether the light is from science, magic10, or something else altogether, it should make things be even more riveting. The fetishism of science has made mystery writers forget why readers love to read their stories. We want investigation, not displays of the authors' intelligence. It's enthralling to pretend you're a detective because stories can be fun and have dank plot twists. And we should be searching for more exhilarating premises, even at the expense of facing real ghosts in our realistic mystery fiction.

Fiction is the realm of imagination, so we should just go wild with it. After playing this title, I want to see more mysteries where the authors invite readers to dream together something truly inventive and thrilling.

It is after all the enabling of curiosity that makes anything mysterious and worth investigating.

Dorothy L. Sayers, a famous mystery writer, once addressed in her Oxford lecture titled “Aristotle on Detective Fiction” that the UK justice system might mistake this fiction as too influential and poisonous for children. But she asserts that “detective writers prefer to think with Aristotle, that in a nerve-ridden age the study of crime stories provides a safety-valve for the bloodthirsty passions that might otherwise lead to murder our spouses.” She argues that realistic detective fiction follows the precepts of Poetics and they can inspire readers with the virtues of the detective. The more accurate a mystery is, the more potent its story becomes. See: Sayers, D. L. (1936). ARISTOTLE ON DETECTIVE FICTION. English, 1(1), 23–35. doi:10.1093/english/1.1.23 pp.25.

Sparling, T. (2011). “Rationalism and Romanticism in Detective Fiction”, Anderseits, Vol 2. No. 1. pp.204

Kastel, “ディスコ探偵水曜日 — You are the Cause By Which I Die” (2016) and Danganronpa and the History of Mysteries — A Newer World Order (2017). Tanoshimi.xyz.

Shirazi, N. and Johnson, A. “Episode 94: The Goofy Pseudoscience Copaganda of TV Forensics”. Transcription by McAslan, M. Citations Needed.

Kastel, “Zaregoto Series: An Introduction to Shinhonkaku Mysteries and Nisioisin” (2018). Mimidoshima.

シェループ (@shelloop), “懐かしさと新しさが交差する”力作”コマンド選択型アドベンチャーゲーム『怪異ホラーミステリー「星影の館殺人事件」』” (2023). Mogura Games.

“This view of the mystical evocation of reality as prominent in detective fiction is an idealistic interpretation that would work if an author were capable of keeping it in

the distant background and only lightly touching upon it through imagery or other stylistic devices. However, most detective fiction that does incorporate principles of romanticisms treats them as primary themes that clash with any possibility of a true detective recipe.” Sparling, T. “Rationalism and Romanticism”. pp. 205

For a historical perspective on how influential Portopia is, see: Parish, J. “Portopia Renzoku Satsujin Jiken retrospective: Beefing in Kobe”. NES Works Gaiden, No. 48.

I am fully aware of Portopia/FamiTan all-kana re-imaginings like the ミステリー案内 (Mystery Annai) series, which may have different approaches to storytelling and could be easier to read on the eyes.

I am reminded of the Nippon Ichi horror game visual novels series, 流行り神 (Hayarigami), which tasks the player choices that will change how the mystery is perceived. Players could opt to interpret the facts of the case as either scientific or occult, but the full story can’t be understood without reading both parts. As a result, I never viewed it as a mystery series but something akin to a “philosophy of mystery”.

Just a small thing, but I kinda like weird Japanese words/kanji reading like Kowabamidori. I can see where it comes from, but man that is a weird word.

All kana sounds like a bitch to read and translate tho ngl