CRYMACHINA: An Antihumanist Plea for Life and Liberation

this is not a parade, it's a protest march

On October 24, 2023, Kyodo News reported that

Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida on Tuesday remained cautious about legally recognizing same-sex marriage and allowing married couples to take separate surnames, as opposition lawmakers grilled him on issues ranging from the economy to gender equality at the start of an extraordinary parliamentary session.He asks that lawmakers pay attention to developments in gay rights litigation, parliamentary debates, and what's happening in local governments.1

Kishida should heed his own advice: movements like Marriage for All Japan have made it clear that discrimination against sexual minorities persists because of their inaction; same-sex partners, for example, are not legally allowed to visit their loved ones in the hospital because “they may not be considered family.”2 The Japanese public is also on-board with gay marriage3 and many cities and regional prefectures have handed out partnerships as a compromise.4 When the city of Tokyo started processing partnerships in 20225, it's hard to imagine that Kishida and his cronies couldn't hear all the chants for gay rights outside their workplace. They clearly don't see gay people as deserving of human rights.

And yet, everyone must keep on begging: please, Liberal Democratic Party, please reconsider. Even the justices of the Japanese Supreme Court cannot do much without requesting this stubborn, conservative force to rewrite the Constitution.6 Nothing seems possible until the LDP will recognize sexual minorities as fellow humans.

But do sexual minorities really need recognition from the people who hate them? Do they need a reason (legal or moral) from politicians to justify their existence? Do gay people really want to be recognized as “human beings” the same way these monsters are?

Crymachina dares to ask these questions through a science fiction allegory.

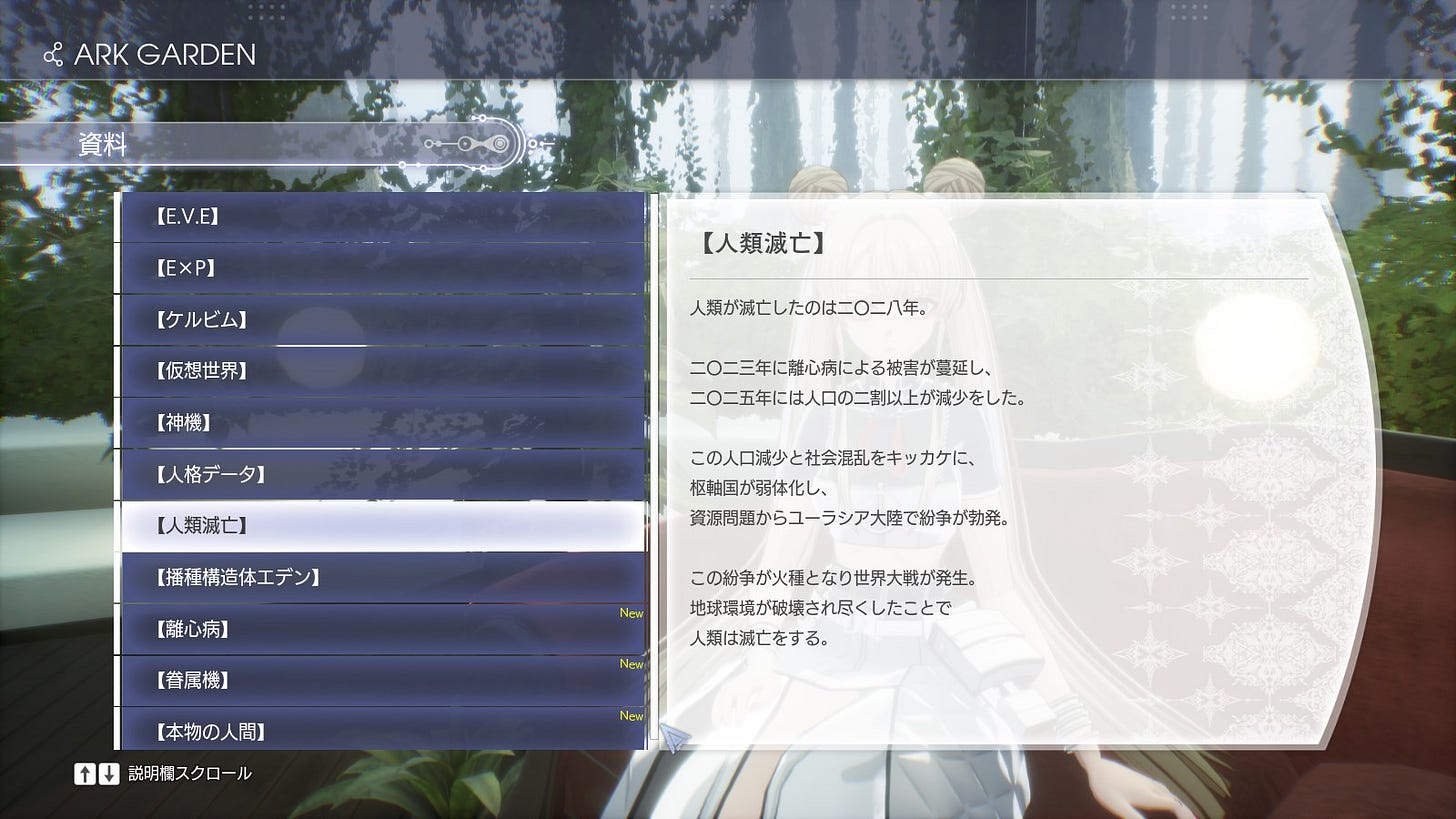

In the game, humanity has been wiped out by a mysterious pandemic and subsequent wars, but they are able to send Eden, a spaceship full of automatons that can be activated by the digitized consciousnesses of past humans. Eden is humanity's last hope: if the project succeeds, humans will once again roam the stars. We follow a group of automatons whose only goal is to become "real people" in the midst of a civil war between Enoa and other dei ex machina.

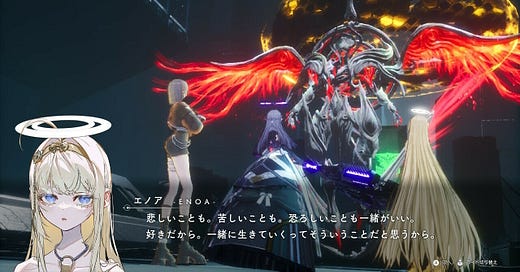

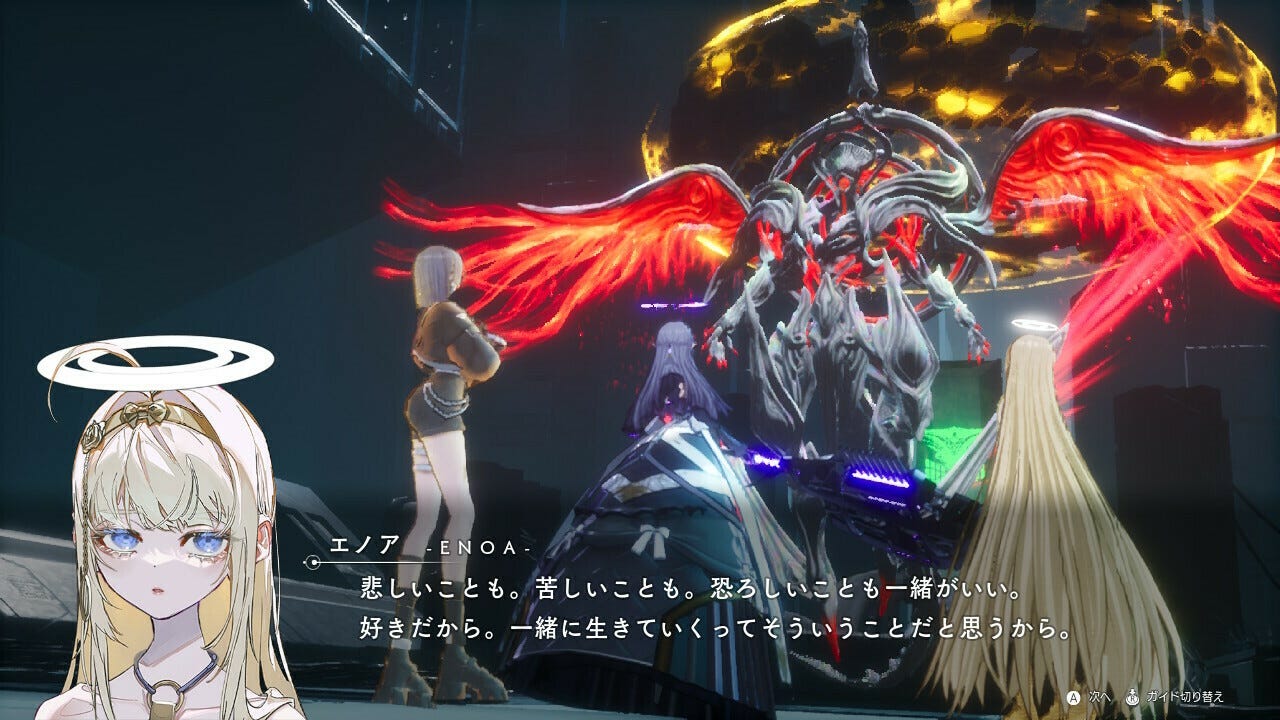

But while the story feels like it's playing with typical science fiction tropes, it's more concerned with the meaning of humanity in face of emergence and generalized artificial intelligence. The cast is amazed by humanity’s ingenuity and technological prowess, but the main protagonist Leben can’t stand the hypocrisy of humans: they destroy, they hurt, they crush to live. She prefers the simplicity of machines and is attracted to Enoa, the “angel” dea ex machina who materialized her. Machines like Enoa are kinder and more compassionate than the people Leben has seen in her past human life.

The other two characters, Mikoto and Ami, have known each other for a while and they’re clearly in a relationship. Ami is in love with everything about Mikoto: she admires Mikoto’s coolness, her passion for movies, and her little embarrassing weaknesses.

But Mikoto is evasive about returning Ami’s affection. She doesn’t want to settle down just yet, resulting in a noncommittal romantic relationship. Nevertheless, she’s more than happy to embrace Leben, Enoa, and Ami as family members as they fight automatons injected with partial human consciousness.

We learn a lot about this family of two lesbian generations. Most of the game involves less combat and more so-called tea parties where characters make small chat about their likes and dislikes or what they have just encountered. We read their banter: Leben thinks whales are cute, Enoa think it’s important to remain robotic regardless of the situation, Ami looks privileged but is very into instant food, and Mikoto has terrible taste in movies. Interactions like these make it tempting to call the characters human-like.

But humanity is an oxymoron: we also read documents and memories of defeated automatons that describe the lengths to which humans will go to preserve themselves. The apocalypse forced people to conduct research through unethical means like reanimating corpses and animal experimentation, some of which read like Twilight Zone parodies. We never know the extent of what happened before the game began, but we can know for certain there was much destruction.

The more the protagonists begin to gain sentience, the more they have to reckon with the fact that humanity is not the ideal they've been working for. Capitalists and politicians look out only for themselves; everyone else is a tool, a machine to be used for selfish gain. And for the people who don’t conform to the demands of the power elite, they are shamed, vilified, and most importantly dehumanized.

Our protagonists are also rated with the same rubric: they may be recognized as sentient and even as having a soul, but they will never be considered human. Being human is not about consciousness or emotions; it is a political category, a value-judgment that exists to exclude and oppress others. Humanity is a system of oppressive social relations that categorizes those who fit in and follow societal rules from those who don’t. Subjection, colonization, violence — exterminating the Other is part and parcel of what makes us human.

This is the humanity that we gain when the colonizers and capitalists of the world decide to recognize us. When they grant us humanity, society doesn't change to accept us; we simply gain privileges and rights that make it easier to navigate the oppressive structures that hurt us7. Humanism is the lie we tell ourselves that the continuing stratification is necessary for our advancement as a species8. The illusion has credence only because of our belief in some elusive human condition.

If we muster the courage to shatter this myth, what will happen? What does the end of humanity actually mean?

Crymachina sketches a speculative answer9: it envisions a world without humans as liberatory. Laws disappear, harm withers away; there is no need to create legal categories because differences are no longer the building blocks of society. There are no humans or automatons or animals, only loving beings. But their love cannot demand reciprocity. The second they calculate how they should love and give back, it becomes false10 and susceptible to the “human” impulse for recognition/compensation. It is not eugenics or politics but pure, unrequited love that drives their will to live and survive the odds.

We are, of course, speaking in dreams. The world doesn’t exist in Japan or anywhere really; the reality of politicians and capitalists prevents us from reaching this utopia. The Japanese Constitution is not going to rewrite itself.

But we know what needs to be changed. Crymachina is not a parade but a protest march and I’ll be marching in it as long as it takes for us to freely live and love.

Marriage for All Japan, “Marriage Equality”.

Marriage for All Japan, “Same-Sex Partnerships in Japan”.

The Japan Times, “Tokyo begins recognition of same-sex partnerships”.

Lies, E. Reuters, “Japan ruling on same-sex marriage disappoints but 'a step forward'". The Marriage for All Japan disagrees with the justices, pointing to the ambiguous language used in the Constitution and how it doesn’t explicitly deny gay marriage. See: Marriage for All Japan, “Constitution and same-sex marriage”.

Dean Spade has written about how simply reforming hate laws misunderstands the power dynamics against trans people and other minorities in the US context. See: Spade, D. Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics, and the Limits of Law. Glen Sean Coulthard has also argued about the limits of Indigenous struggles in getting recognized by the Canadian state. See: Coulthard, S. Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition.

Sylvia Wynter lays out a critical genealogy of Western humanism, how it shaped our understandings on ontology, and how its “overrepresentation” has affected everything, including our natural sciences. See: Winter, S. “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument”.

Cameron Kunzelman describes the speculative potential, both utopian and dystopian, of the mechanics in science fiction video games. He argues that speculation helps us imagine unthinkable futures, but it can collapse into reactionary ideologies. See: Kunzelman, C. The World is Born From Zero: Understanding Speculation and Video Games.

anymo has written about how the yuri dynamics of Crymachina works and how they differ from other yuri media. See: Den Faminico, 「責任とってね」「地獄の底まで一緒」「あたしと生きてよ」──。少女たちの“巨大感情”をあまりにも濃密に描いた『クライマキナ』が関係性オタク大歓喜の一作だった.