Common'hood: Figuring Things Out Together

what if we allow ourselves to think together... omg...

A World Without Homes

Anyone who reads a lick about capitalism will inevitably find themselves engaged in talks about the housing crisis in the Global North. Stories of eviction are plentiful, despite this whole pandemic thing going on. We are also supposed to welcome “urban renewals/regenerations” projects into our neighborhoods; parks, transit, and other facilities displace long-time residents and increase property value for real estate gamblers. These practices and more undergird gentrification, the process of transforming an otherwise poor neighborhood through the invasion of the rich and wealthy1.

As a result, it is almost impossible to avoid having a personal experience or two. While navigating my way through the confusing world of letting agents, I questioned the prospects of anyone in academia paying the bills. Years later, my distress was confirmed upon reading an article about how a professor lived in a tent2. In the last few months, I had to also help people (one from the United States and another from the UK) secure housing because their landlords and real estate agents were — to use academic jargon — a piece of shit.

This remains a culture shock for me as I grew up in Singapore, a country with a robust public housing system3. While its implementation through the clearance of burned down villages is certainly controversial4, the public housing system works as a kind of social welfare5. A naive observer may suggest this is the best option to avoid a crisis. And yet, surveying the history of council housing in the United Kingdom reveals that these “municipal dreams” to house everyone can be tainted with the usual combo of hubris and neglect from politicians and planners6. Indeed, Singaporeans are dabbling in a resale market for public housing and the country is now seeing “the rise of million-dollar public housing”7. That is a ticking time bomb that may cause many people to be homeless and poor.

But make no mistake, the housing crisis is not endemic to the Global North: it is a global pandemic8. I don’t have to look far as Jakarta, the city I live in, is responsible for kicking out people who have no choice but to squat in fancy places like the BMW Park9. It is unnerving to think about how many young people here are homeless or on the verge of it during the pandemic10. So much could be done to alleviate the suffering here, but no one seems to care.

As Madden and Marcuse write:

Housing crisis is a predictable, consistent outcome of a basic characteristic of capitalist spatial development: housing is not produced and distributed for the purposes of dwelling for all; it is produced and distributed as a commodity to enrich the few.11

Perhaps then, it is worth pondering about the general state of crises. If a crisis is the general unreliability of states and institutions in reproducing what’s needed to sustain life, then “it can be fixed only through radical measures, which include developing new relationships and new or renovated institutions out of what already exists.”12

That sounds good, but what are these radical measures? What are we supposed to do when it comes to the housing crisis?

Who Knows?

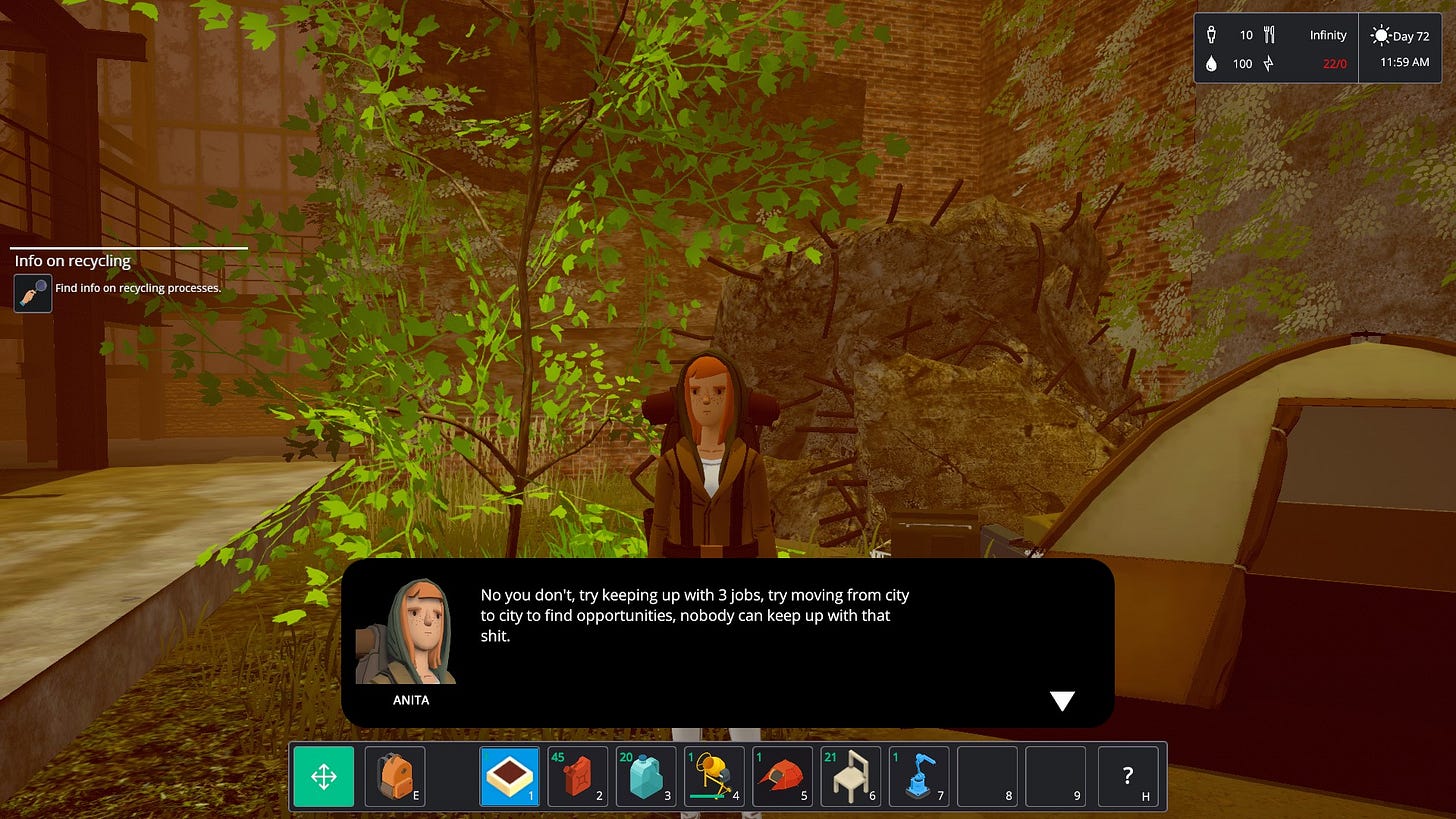

Common’hood, a game developed by Plethora Project and funded by Kowloon Nights, answers, “Who knows, let’s figure it out together.” Released on 10 November, 2022, the game has so far received a mixed reception. Many players were disappointed by the lack of polish and linear gameplay, but some others including myself were able to overlook some admittedly glaring mistakes and find ourselves contemplating about these questions on housing and more.

The player controls Nikki who’s recently lost her home and she has aimlessly wandered into the factory warehouse her dad used to work in. When she finally enters the space, she is surprised to learn that there are people already living there. Nikki is unaware of concepts like “squatters” (people who are setting up residence in an abandoned space)13, so she tries to get up to speed. That means she (and the player) is incentivized to make herself useful. After talking to her skeptical neighbors, she whips out her late father's tablesaw and starts making wood in order to build and sell chairs.

What for?

To make money to buy welding tools.

What will you be using it for?

To repair the workbench.

What’s the workbench for?

To make something someone needs right now.

Contrary to the many misleading articles from the Game Writing SEO Industry, this game is not about the Do-It-Yourself subculture interspersed with gameplay from The Sims or Animal Crossing. Rather, it is a narrative-driven game where you and Nikki are always building toward something, an abstract goal in mind.

But figuring out what this goal exactly entails: well, you’re on your own, Nikki.

Ambivalences

Common’hood is hostile toward any form of hand-holding: it lacks tutorials or directives past the first hour or so. You are only given a quick runover of the basic controls before you have to fiddle with the game’s clunky UI and flag system.

As you progress through the factory and move your encampment into newer zones, you and Nikki will also meet other squatters who question your intent and push you away. Some of them will also be shocked and angry that you actually cleared the path to their tents because they intentionally blocked these entrances off. After all, they’re squatters who may be doing it out of survival needs, not leftist politics. They’ve become more susceptible to threats of eviction and police violence from Nikki’s (and your) actions. It doesn’t feel right to intrude into their spaces and invite them into your collective. If the game didn’t provide a tutorial suggesting these characters could be recruitable, I’m sure many players would want to move on.

And if you want to recruit them anyway, you will need to do some peculiar missions. These tasks are also provided by existing members of the commons; fulfilling their needs increases their trust, which advances their storyline and allows you to delegate more responsibilities for them to do during the day. But clear instructions are nowhere to be seen. Players are often exasperated to learn that these objectives can’t be fulfilled immediately.

And the things you build for them aren’t directly useful to you anyway. Why does Nikki need to make a barbecue grill for this one guy? All you really need to do is just farm a lot of potatoes — or in my case, I acquired an incredible glitch where I have an infinite supply of onions. Food scarcity be damned, we’re all going to have stinky mouths instead.

While the game certainly needs more polish, I argue this mishmash of intentional decisions and unintentional jank is intoxicating because it serves to make the player ask one thing, “What the hell are you doing?”

You’re doing something, but what is it? This “something” keeps eluding Nikki and the player. And it’s not like Nikki has a clear goal in mind either: she knows it’s something, but that’s it. And even if she comes across the concept of commons, can she and the player really practice it?

All you’re doing is fumbling about and trying to get all your research grounds covered. Take, for example, the goddamn barbecue grill I kept complaining about: it required me to build a Lvl 2 Research Chair. I grumbled as I figured my way around the prerequisites of overcoming this very silly obstacle. I didn’t understand the purpose of this mission and it wasn’t like useful anyway.

But it is this utilitarian and productivist mindset the game wants the player and Nikki to interrogate. Why am I so biased against a BBQ grill? Does it matter if it’s useful?

Midway through the game, Nikki stumbles upon a character named Al. He’s just chilling in some tunnel with a deer. Sensing he’s got a lot of experience in doing the things that Nikki wants to do, she says the commons could “use someone like [him] around”.

Al immediately reprimands Nikki for her productivist mentality and sends her away with a book on mutual aid. She (and the player) realizes this is probably what she wants to do, but she's just ignorant. Nikki admits she is naive and prone to expending effort in reinventing the wheel.14

This interaction, among many others, encapsulates what the game is about: there are no clear answers on what a commons should be, so we need to dialog. When activists try to define commoning15, they are conversing with you. In these dialogs, you must confront these ambivalent tensions, including romanticizing squatters and their "nomadic lifestyle".

You are, in fact, being invited to envision commoning practices together in Common’hood, just with fictional characters. These characters want to start anew because they’re broken people wanting a new home. Relationship abuse and grief have propelled their desire for change. The more you learn about them by successfully clearing their missions, the more you realize they have their own vision of what this commons should be.

In other words, you have to work together to envision this utopia. And this trust is scary. What if you break their word and play into the hands of the capitalists?

There’s no WikiHow in distinguishing Good and Bad Leftism. This ambivalent tension never goes away in this game because you don’t know if you are doing something good or not. All you know is that you’re doing something.

And as you go further into the game, you are approached by a group of people wearing gas masks. They call themselves the “Ant Farm” and they keep reminding Nikki there are risks in achieving what might be an unattainable goal. Look at the factory for example: they created this sinkhole that’s still pulling land down. What if your actions might do something similar?

No one knows. Indeed, it is a risk to do something — or anything. We don’t have to rock the boat and we could possibly save more lives that way. But if change is necessary, then we have to take risks to accomplish this change. We need to revisit fundamental assumptions about work and society if we intend to value everyone's input.

Narrative Criticism

If anything, my criticism of the game's narrative is that this tension around commoning could be more ambivalent.

For example, I can imagine the inclusion of Indigenous voices complicating the whole idea of commoning. It would've been interesting to see how squatting is linked to settler colonialism16. This would challenge players into interrogating what it means to have property rights, to possess something, and so on especially in the context of a commons. Can a commons exist ethically on stolen Indigenous land? The continual dispossession of land is worthy of discussion, especially in the context of environmental criticism in a settler colonial state like the United States17. Although the game brings up and celebrates the traditions of minorities, there is a noticeable dearth of discussions on how race is connected to property. Whiteness is especially linked to property in settler colonial states18.

If commoning is to be taken seriously, then it must challenge the ontological assumptions of property. Otherwise, leftists may be prone to enacting another form of settler colonialism, just dressed in more radical language19.

A Common Mind

Nevertheless, I find myself enamored by Common’hood. It reproaches naive radicalism for not studying history while working and hoping toward a better future. In this sense, the game is in keeping with Mariame Kaba’s notion of “hope is a discipline”; it’s tough work to imagine a world without police20 or, in our case, homelessness. We have to critique and learn from each other to advance our abstract goals and realize our almost impossible dreams of commoning.

It is thus refreshing to encounter a game where the creators are this self-critical. While their prose lacks finesse and polish, they have focused their storytelling prowess into elaborating the interplay between gameplay and narrative. Once the player gets it, the game is some powerful stuff.

That said, Common’hood is not an easy game to recommend or write about for that matter. It’s full of bugs and questionable game decisions while sporting an irritating lack of QOL. You need a lot of good faith and a Discord account connected to their server in order to navigate through this mess.

But what it does possess is an ethic that I would like to see more in games: critical reflections on progressive ideas that are tied successfully to gameplay and narrative design decisions. This leads the player to reflect, critique, and revise their actions.

And this dialog — whether it’s between the player and a game or between people — is the first step in connecting theory to action.

Samuel Stein is a New York city planner and he criticizes his field for being an accomplice to what he calls the “real estate state”. See Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State (London: Verso Press, 2019). Leslie Kern has also written a book that debunks myths by providing an overview of the literature on gentrification. See Gentrification is Inevitable and Other Lies (London: Verso Press, 2020).

Anna Fazackerley, “‘My students never knew’: the lecturer who lived in a tent.” Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/education/2021/oct/30/my-students-never-knew-the-lecturer-who-lived-in-a-tent. Accessed 27 Nov. 2022.

Sock Yong-Phang and Matthias Heible, “Housing Policies in Singapore.” ADBI Working Paper 559 (Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute, 2016). https://www.adb.org/publications/housing-policies-singapore

Loh Kah Seng, “The Politics of Fires in Post-1950s Singapore and the Making of the Modernist Nation-State.” In Reframing Singapore: Memory - Identity - Trans-Regionalism, edited by Derek Heng and Syed Muhd Khairudin Aljunied, 89–108. Amsterdam University Press, 2009. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt45kf1j.9.

Robbie B. H. Goh, “Ideologies of ‘Upgrading’ in Singapore Public Housing: Post-Modern Style, Globalisation and Class Construction in the Built Environment.” Urban Studies 38, no. 9 (2001): 1589–1604. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43196729.

John Boughton, Municipal Dreams: The Rise and Fall of Council Housing (London: Verso Press, 2019).

Chen Lin, “Singapore sees the rise of million-dollar public housing”. Reuters (2022), https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/singapore-sees-rise-million-dollar-public-housing-2022-08-31/. Accessed 27 Nov. 2022.

Mike Davis, Planet of Slums (London: Verso Press, 2017). Steffen Wetzstei, “The Global Urban Housing Affordability Crisis.” Urban Studies, vol. 54, no. 14, 2017, pp. 3159–77. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26428376. Accessed 27 Nov. 2022.

“City tells squatters to leave BMW Park.” Jakarta Post (2017). Accessed 27 Nov. 2022. https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2017/05/22/city-tells-squatters-to-leave-bmw-park.html

Nina A. Losana, "Thousands of Jakartans pushed to brink of homelessness by COVID-19 pandemic: NGOs". Jakarta Post (2020). Accessed 27 Nov. 2022. https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/05/06/thousands-of-jakartans-pushed-to-brink-of-homelessness-by-covid-19-pandemic-ngos.html

David Madden and Peter Marcuse, In Defense of Housing (London, Verso: 2016) pp. 10-11

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), pp. 26.

Squatters Handbook, 13th Edition (London: Advisory Service for Squatters, 2009). For an overview on urban squatting and how it ties to leftist politics, see Alexander Vasudevan, The Autonomous City: A History of Urban Squatting (London: Verso, 2017).

For a quick explanation on mutual aid, see Dean Spade, Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis and the Next (London: Verso Press, 2020). For anti-work critiques of productivism and how it ties to mutual aid, see David Frayne, The Refusal of Work: The Theory and the Practice of Resistance to Work (London: Zed Books, 2015).

Julie Ristau, “What is Commoning, Anyway?” On the Commons. https://www.onthecommons.org/work/what-commoning-anyway

Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang. “Decolonization is not a metaphor”. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society Vol. 1, No. 1, 2012, pp. 1-40.

Glen Sean Southcard reinterprets Karl Marx’s notion of primitive accumulation and David Harvey’s accumulation by dispossession in the context of colonial theft of land. See Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014). pp. 7-15. Robert Nichols, on the other hand, distinguishes dispossession from primitive accumulation. See “Marx, after the Feast” in Theft is Property!: Dispossession and Critical Theory (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020). On how land theft is connected to environmental science, see Max Liboron, Pollution is Colonialism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021).

Cheryl Harris, “Whiteness as Property.” Harvard Law Review, vol. 106, no. 8, 1993, pp. 1710-1791. Aileen Moreton-Robinson, The White Possessive: Property, Power, and Indigenous Sovereignty (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015).

Scott Laura Morgensen, “Un-Settling Settler Desire.” In Unsettling Ourselves: Reflections and Resources for Deconstructing Colonial Mentality edited by Unsettling Minnesota Collective (2009). pp.156-157.

Mariame Kaba, We Do It ‘Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2021).

I didn't know you're in Jakarta as well! It's always so weird whenever I follow some random content creators like Rong Rong and Ignideus, then suddenly I found out you're in the same country as I am.

It feels so weird, because I always felt like the content I'm interested in diverges strongly from what most people around me interested in, so it's always jarring and cool whenever I find that, yes, there are people with very similar interest to me in this country.

Regarding Jakarta, having lived here for the last three years, I think it's comparatively mild compared to other countries. Kost here are easy to get, at various pricepoints. And people are very willing to help each others, though the opposite also means that they sometimes implicitly ask for "something" (money) for their help.

At the same time, I'm not blind that there's a real lower class whose life just... sucks, and barely make ends meet. But whether by force or cooperation, they do often end up as groups from what I see -- it's quite often that pengamen/street musicians are part of a larger group and/or travel together, and I hear the waria/queer community are very close-knit with each others.

I think the most depressing thing is the lone silverman beggars. I sometimes just see them sitting down and looking tired, after they walked around, begging, and debasing themselves looking... I don't know, looking awful drenched in what is probably toxic paint.

Really great article, I appreciate the thorough citations! I haven't played Common'hood yet (and judging by the bugs I may want to wait), but it's great to see games posing these hard questions, and acting as a dialog rather than a lecture.